What is all this stuff? What does it mean? Why is it here and why am I here? What the hell should I do?

These are a few of the largest and most troubling queries of human existence—questions which have tantalized and terrified our sophisticated ape-brains since time immemorial. Philosophy, religion, art, and science—the classic cornerstones of human culture and society—were all born from our desire to explore and/or solve these fundamental-yet-inscrutable puzzles.

But, despite thousands of years of inquiry, observation, analysis, and countless attempts at explanation, the absolute answers—the truths with the capital Ts—arguably elude us as completely as ever, like little imp-gods always darting into the shadows, sniggering at those silly bipeds of the ever-curious species, Homo sapiens.

The good news is this: many, many brilliant answers have been formulated, and countless maps have been drawn by those before us to elucidate the problems of human existence as well as the factory-approved methods for navigating this oft-absurd world (even its modern incarnation as globalized labyrinth complete with Internet rehab, child celebrities, and boob jobs). We may not be able to know the Ultimate Shiny Golden Truth, but life might be okay without it.

Viktor Frankl: A Cool Cat

Viktor Frankl, an Austrian neurologist and psychiatrist, was one fellow who laid out a particularly compelling roadmap in the form of a book, Man’s Search for Meaning

Viktor Frankl, an Austrian neurologist and psychiatrist, was one fellow who laid out a particularly compelling roadmap in the form of a book, Man’s Search for Meaning. The book, which has been read and celebrated by tens of millions of people, is equal parts memoir and philosophy.

It chronicles Frankl’s experience as a concentration camp prisoner during the Holocaust, paying particular attention to how people sustained themselves (or didn’t) in the most dire of situations—what gave the inmates a sense of purpose and conversely, what caused them to lose all will to live. The book then details the central principles of logotherapy, Frankl’s school of psychotherapy which he developed after surviving WWII.

Logotherapy is based on existential analyses of patients’ lives and operates under the belief that Kierkegaard’s will to meaning is the underlying guiding principle of human behavior (as opposed to Nietzsche’s will to power or Freud’s pleasure principle). Basically, Frankl thought that what we all salivate for and require in the deepest recesses of our being is for our lives to have meaning—i.e. worth or significance—and that our actions are primarily in service of finding this meaning.

“Existentialism” is a broad term lumped upon a group of wildly different philosophers because they all concern themselves with a similar sort of experience: a feeling of disorientation, despair, anxiety, and/or confusion in the face of a seemingly meaningless or absurd universe. These philosophers (of which the most famous are probably Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Camus, Sartre, and Dostoyevsky) attempt to define the various aspects of this dilemma and consider how to resolve it, suggesting that to arrive at meaning we ought to do things like create our own values, live “authentically”, rebel against power structures, etc., etc.

Thus, logotherapy is an existential school of psychotherapy because it views psychological distresses or difficulties as deriving primarily from this inability to find significance in one’s actions, relationships, or life. Its methods aim to help patients re-discover a sense of worth and purpose in their ideas of the past, present, and future. In Man’s Search for Meaning, Frankl carefully elaborates the philosophical underpinnings of logotherapy, the ideas which took shape during his time in concentration camps.

Show Me the Meaning of Beeiiinnngg… Human

Like other existential philosophers, Frankl believes that searching for an abstract, universal meaning of life is futile. He writes:

“Ultimately, man should not ask what the meaning of his life is, but rather he must recognize that it is he who is asked. In a word, each man is questioned by life; and he can only answer to life by answering for his own life; to life he can only respond by being responsible.”

Frankl suggests that rather than searching beyond ourselves for some revelation of the meaning of life, we must realize that only we can provide the answer. Life is seen as a challenge and an opportunity to define worth for ourselves, to find our own unique, jazzy boysenberry nectar through our thoughts and actions. If we accept and affirm existence, we have necessarily taken on a responsibility to discover and continually replenish the sense of meaning that we require.

Frankl touches upon the fact that some philosophers would deny that man possesses any real degree of freedom in his ability to find meaning. Some claim that we are nothing more than an accidental result of biological and psychological processes and environmental factors, devoid of free will. Frankl rejects this:

“But what about human liberty? Is there no spiritual freedom in regard to behavior and reaction to any given surroundings? … Most important, do the prisoners’ reactions to the singular world of the concentration camp prove that man cannot escape the influences of his surroundings? Does man have no choice of action in the face of such circumstances?

We can answer these questions from experience as well as on principle. The experiences of camp life show that man does have a choice of action. … Man can preserve a vestige of spiritual freedom, of independence of mind, even in such terrible conditions of psychic and physical stress.

We who lived in concentration camps can remember the men who walked through the huts comforting others, giving away their last piece of bread. They may have been few in number, but they offer sufficient proof that everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms — to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”

For Frankl, there are three basic ways that we arrive at meaning:

“Thus far we have shown that the meaning of life always changes, but that it never ceases to be. According to logotherapy, we can discover this meaning in life in three different ways: (1) by creating a work or doing a deed; (2) by experiencing something or encountering someone; and (3) by the attitude we take toward unavoidable suffering.”

Frankl holds that meaning is always available to us, if we are in the correct frame of mind. We might locate value or significance at any time, and for Frankl, there are three primary ways that this tends to happen: through creation or action, through experiencing/loving the world and other people, and through our attitude toward the inevitable distresses of human life.

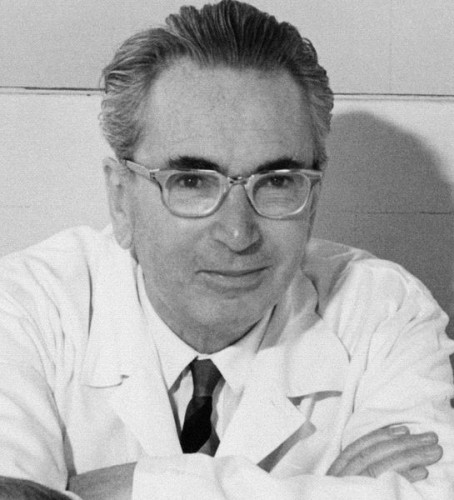

Dr. Viktor Frankl, 1965. Photo Credit: Wiki Commons

Make! Do! Experience! Love!

Frankl doesn’t dedicate nearly as much writing to his first two means of meaning-discovery as he does to the third because he sees the third way as the one that is always available (even to a concentration camp inmate) and thus most essential. Of the first two means, he writes:

“An active life serves the purpose of giving man the opportunity to realize values in creative work, while a passive life of enjoyment affords him the opportunity to obtain fulfillment in experiencing beauty, art, or nature.”

Related to this, Frankl references the psychotherapist Edith Weisskopf-Joelson, who wrote that logotherapy emphasized that experiencing something in passive contemplation is as equally valid and meaningful as making or achieving something. Logotherapy aims to compensate for our cultural obsession with external achievement by validating and celebrating the inner world of experience. I’m reminded of a quote from Borges: “Let others pride themselves about how many pages they have written; I’d rather boast about the ones I’ve read.”

Later in the book, Frankl writes:

“By declaring that man is responsible and must actualize the potential meaning of his life, I wish to stress that the true meaning of life is to be discovered in the world rather than within man or his own psyche, as though it were a closed system. I have termed this constitutive characteristic “the self-transcendence of human existence.” It denotes the fact that being human always points, and is directed, to something, or someone, other than oneself—be it a meaning to fulfill or another human being to encounter. The more one forgets himself—by giving himself to a cause to serve or another person to love—the more human he is and the more he actualizes himself.”

So for his first two means of meaning-discovery, Frankl sees forgetting oneself as the essential ingredient that contributes to the discovery of meaning. Meaning is found when we give ourselves over to the world—to our work, our contemplation, our loved ones, etc.—entirely, when we lose ourselves in all that is not us, thereby communing with the world. At various times throughout the book, Frankl muses further on the power of love in particular:

“Love is the only way to grasp another human being in the innermost core of his personality. No one can become fully aware of the very essence of another human being unless he loves him. By his love he is enabled to see the essential traits and features in the beloved person; and even more, he sees that which is potential in him, which is not yet actualized but yet ought to be actualized. Furthermore, by his love, the loving person enables the beloved person to actualize these potentialities. By making him aware of what he can be and of what he should become, he makes these potentialities come true.”

Frankl holds that through our love for others we allow them to understand the potential housed within them. For him, love is a necessary key to reaching and actualizing the dormant meaning that we are capable of bringing into the world.

Courage and Humor in the Face of the Shit-Storm

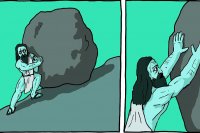

The final means of meaning-discovery that Frankl discusses in-depth is man’s ability to decide how to bear his suffering. Frankl asserts that suffering is inevitable in life, but that we can realize a profound meaning in the way we approach this truth:

“If there is a meaning in life at all, then there must be a meaning in suffering. Suffering is an ineradicable part of life, even as fate and death. Without suffering and death human life cannot be complete.

The way in which a man accepts his fate and all the suffering it entails, the way in which he takes up his cross, gives him ample opportunity—even under the most difficult circumstances—to add a deeper meaning to his life. It may remain brave, dignified and unselfish. Or in the bitter fight for self-preservation he may forget his human dignity and become no more than an animal. Here lies the chance for a man either to make use of or to forgo the opportunities of attaining the moral values that a difficult situation may afford him. And this decides whether he is worthy of his sufferings or not. … Such men are not only in concentration camps. Everywhere man is confronted with fate, with the chance of achieving something through his own suffering.”

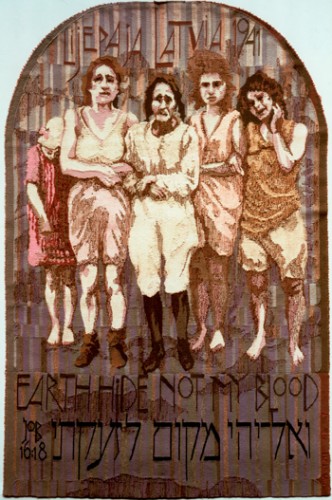

Daughters of Earth, Holocaust series, Muriel Nezhnie and Sheldon Helfman’s personal collection. Photo Credit: Wiki Commons

Frankl argues that we often view suffering as something to be ashamed of or as proof that we are weak-minded, when in fact suffering is unavoidable and should give us a sense of pride and dignity in our ability to summon strength and bravery in the face of life’s proverbial shit-storms. He suggests that every day, we are faced with a decision: a decision to either bemoan the circumstances of our lives and allow them to slowly crush us, or to exercise our ability to calmly accept what cannot be changed, to remain mentally free and upright:

“Every day, every hour, offered the opportunity to make a decision, a decision which determined whether you would or would not submit to those powers which threatened to rob you of your very self, your inner freedom; which determined whether or not you would become the plaything of circumstance, renouncing freedom and dignity to become molded into the form of the typical inmate.”

Frankl also comments on the usefulness of cultivating a sense of humor as a means of overcoming despair:

“Humor was another of the soul’s weapons in the fight for self-preservation. It is well known that humor, more than anything else in the human make-up, can afford an aloofness and an ability to rise above any situation, even if only for a few seconds.

[…]

The attempt to develop a sense of humor and to see things in a humorous light is some kind of a trick learned while mastering the art of living. Yet it is possible to practice the art of living even in a concentration camp, although suffering is omnipresent.”

Existential Vacuum: Yikes, It’s Hard to Breathe

Frankl discusses the pervasive nature of an “existential vacuum” in the twentieth century:

“The existential vacuum is a widespread phenomenon of the twentieth century. This is understandable; it may be due to a twofold loss which man has had to undergo since he became a truly human being. At the beginning of human history, man lost some of the basic animal instincts in which an animal’s behavior is imbedded and by which it is secured. Such security, like Paradise, is closed to man forever; man has to make choices. In addition to this, however, man has suffered another loss in his more recent development inasmuch as the traditions which buttressed his behavior are now rapidly diminishing. No instinct tells him what he has to do, and no tradition tells him what he ought to do; sometimes he does not even know what he wishes to do.”

Frankl notes that in recent history, human culture and society have experienced a rather radical shift in consciousness. A period has ensued in which many of our old idols and traditional systems of belief have been discredited or called into question by science and new means of disseminating information. In this postmodern world, there is little agreement as to what is meaningful. We are freer than ever to decide for ourselves what to value and how to act.

But there’s a problem with this: being free is fucking frightening and paralyzing. Kierkegaard wrote that “anxiety is the dizziness of freedom.” How are we to decide what to do and what to value when there are nearly infinite possibilities? It’s an overwhelming task. So, many of us opt to passively drift along, allowing societal structures and the opinions of others to dictate our actions. Yet, according to Frankl, this is ultimately a sacrifice of our freedom and leaves us with a sense of emptiness and despair; we have not sought to find meaning for ourselves and have thus manifested a life that feels devoid of something, boring, inconsistent with ourselves: an existential vacuum.

Though it might be uncomfortable and strenuous to do so, we can only alleviate this situation by taking responsibility for discovering meaning in our lives. We must actively seek out what moves our deep-down selves—what we feel arise organically in our inner world (once again, do your thing)—and immerse ourselves in it, while also attempting to recondition our minds to see dignity and value in our confrontations with suffering. This existential approach is arguably the most effective replacement for the certainty that was once given to us by tradition and deities. Although realizing meaning in our lives may now be a greater struggle than at any point prior, we can take solace in knowing that the meaning we do find will be our own, and that through our efforts we will have proven ourselves to be bold, resilient individuals.

Or, heck, conversely, it may be surprisingly easy to find meaning—if we can just let go of our expectations for what our lives might be and appreciate the people around us, the things we’re naturally good at, the simple delights of human existence, and the opportunity to learn and explore amidst the peaks and valleys of this strange life-thing. I don’t know. Maybe.

“I have learned that to be with those I like is enough.”

Walt Whitman

If you enjoyed this piece, consider subscribing for free by email or RSS.

Note: As with all of the book links on this site, if you click through and purchase something on Amazon, I receive a meager portion of the revenue. This goes toward web hosting and site maintenance and is much appreciated.

About Jordan Bates

Jordan Bates is a Lover of God, healer, mentor of leaders, writer, and music maker. The best way to keep up with his work is to join nearly 7,000 people who read his Substack newsletter.

Great reflection, thanks 🙂

No problem, Ninad. Thanks for reading it.

What a great read. I think living a life free from anxiety is a life in denial

Sab,

I’m with you. Anxiety, at least occasionally, seems like a healthy response to our unknowable situation. Cheers.

sense of meaning derived ….must be a good read

It really is. Highly recommend it.

Yes indeed

Jordan what month and what year did you write the Viktor Frankl article? I want to use it as reference for my degree. Many thanks, Sam

february, 2014, i think, Sammy. cool that you’re using it. peace

Buenísimo

thanks Eloisa :)))

[…] you feeling fuzzy, bemused, and more tolerant than ever of humanity’s limitless capacity for meaning-making. There’s just so darn much out there. Busy, busy, […]